ほとんどの人にとって、収入はピークを迎えた

Cover Story 1/4

Less than 100 years ago, if you asked a random person where they had grown up, over half would have answered: "on a farm." Today, you are lucky to ever get that reply, as only 1 in 50 people work in agriculture in most advanced economies[1].

Had you further asked those farmers back then what decided if you were rich or poor, they would have been quick to say that the size of your land and its soil mattered most, and how many good hands, oxen and horses were available to work that land. They too might have mentioned the weather, the right amount of sunlight and water, the absence of pests, and maybe your capability to store and sell your crops. Economic text books, back then, said the same as the farmer.Today, for most of us, our lives revolve around other things. We work in offices or factories, or provide services to people who work in offices and factories. And even if we are one of those rare farmers, what matters most has changed altogether. Farmers work with machines and computers like everyone else, and run that farm pretty much as any other business.

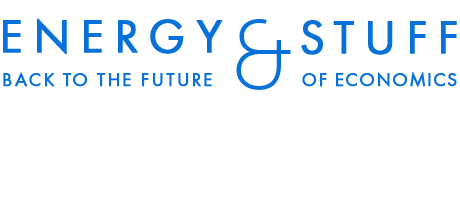

Grain yields per acre have increased massively within a few decades (e.g. corn yields per acre grew 6-fold between 1930 and 2010[2]) If they industrially farm fruit or vegetables in a greenhouse or livestock raised inside, neither the acreage of their land nor the amount of sunlight or rain matter much, just the size of the "factory", how well they manage growing conditions, and avoid pests and diseases.

Why has all this changed completely? Why have we seemingly become so independent from land, sunlight and water to go about our lives? Commonly, this change is attributed to the industrial revolution, specifically the introduction of technology to do things more easily that previously required a lot of manual or animal labor, which brought us luxuries our ancestors never had, such as cars, airplanes, or smartphones. This process started about 250 years ago with the introduction of steam engines in England, and has since spread to every single corner of our planet. We would rather label it "energy revolution", but let's first take a brief history tour.

1800 - 13 years after the U.S. Constitution was born

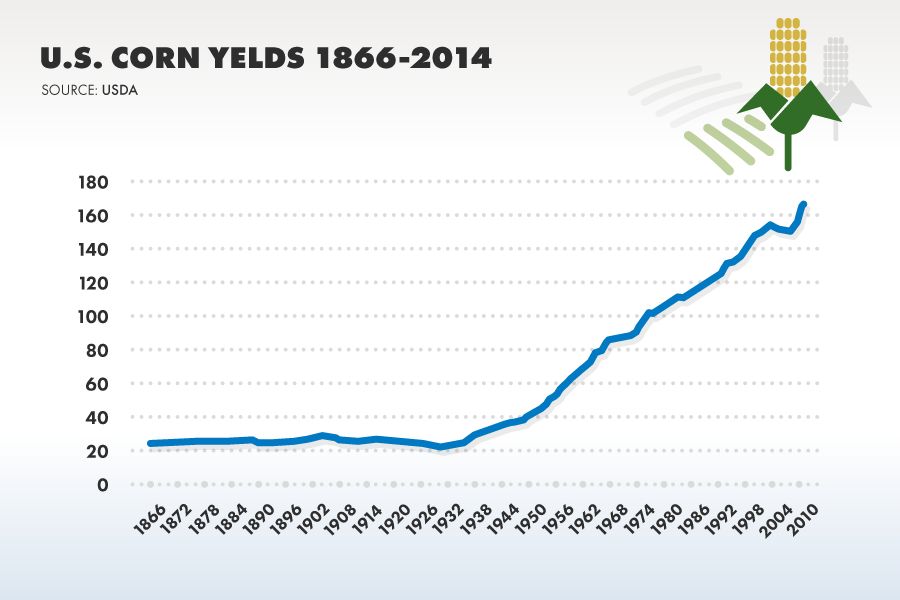

For most people, not much had changed for centuries, about 75% of them were farmers like almost everywhere around the world, working their land with draft animals and their bare hands. A few steam engines had made their appearance in coal mines and factories, but there were no railroads yet, no electricity, and not much else resembling today's advanced societies. Parts of Europe and the newly born "United States of America" were like today among the richest places around the world. But "rich" back then meant that an average person's income was about $2500 in 2015 dollars[3]. That is a little more than $200 a month. Can you imagine living off $200? You have to travel far into the poorer regions of Africa or Asia to find countries with similar per-capita incomes today.

Just for comparison: a full 1800 years earlier, in ancient Rome around 1 A.D., annual average incomes had been around $1500[4] in today's money, only 40% less than in the year 1800. Very little progress for such a long time.

Fast track to 1950 - modern life is here

Only another 150 years later, the average American had experienced a sevenfold increase of his or her inflation-adjusted income. Everything we know today was showing up: cars, planes, TVs, telecommunications, the first computers, and modern farming, feeding more people per acre than ever before. However, farmers still made up more than 12% of the workforce, as many still worked their land the way their ancestors had for centuries.

The Year 2000 - a peak for everyone

Another jump forward by 50 years to the year 2000, and within those short 50 years, per-capita incomes had tripled again.

The bubbles in the left-hand graph show how impressive that development really was. The average American's income was 12 times that of 200 years prior when adjusted for inflation. And the good part was that lower incomes had participated more than anybody else in this rise, making each person the richest person in history within their income range.

The entire world took part in the same growth story, often a little later and less pronounced, or starting from lower levels. From 1820 to 2010, within less than 200 years, global per-capita incomes grew 11 times in inflation-adjusted dollars, while the world population increased from roughly 1 to 7 billion people within the same period. In other words, the entire global economic output is now 77 times larger than what it used to be 200 years ago. Or more precisely: Around the year 1820, almost all of the 1 billion people on our planet lived in poverty by today's standards. Today, a little less than 1 billion people lives in absolute poverty, whereas the remaining 6.5 billion people are doing much better than their ancestors 200 years ago.

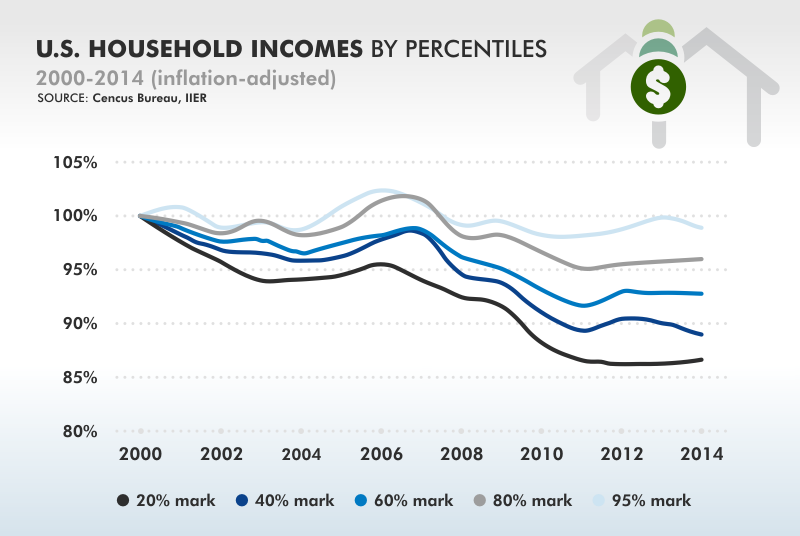

The 21st century - a turning point

During the past 15 years, this amazing growth pattern began to break. It started with low-income earners in advanced economies, and more recently hit almost everyone but the ominous top "1 percent" in those countries (yet even for them, their still growing income figures don't tell the entire story.). Between the year 2000 and 2014, all but the richest U.S. households saw their inflation-adjusted incomes shrink. Recent data shows that in 2015, there was a slight improvement after energy and resource prices had dropped by more than 50%, but that benefit unfortunately isn't here to stay.

Let's try to understand this with a chart: households at the top of the lowest quintile (meaning that 20% of households make less, and 80% earn more), have seen their annual incomes shrink by 14% between the years 2000 and 2014[5], throwing them back to the levels of 1974. Households at the 60% mark (40% have a higher income), lost 8% in those 13 years, pushing their incomes back to 1995. Only households above the 95% level have seen a rise, at least on paper Similar developments can be obvserved in almost all advanced economies during the past decade.

What is particularly remarkable: this decline partly took place during a recovery period after the so-called "Great Recession" following the financial crisis of 2008/9 [6]; despite feverish attempts of governments and central banks to restart the economy, ranging from deficit spending, economic stimulus, to the lowest interest rates in history. This new dynamic is puzzling everyone, but it can be explained by something rarely talked about: we have more or less used up the easily accessible natural resources on our planet with no good replacements in sight, and are now working our way through the hard-to-get ones, which makes continuiong our formindable 20th century growth miracle much more difficult.